On the Cessna 210 series, external hydraulic leaks (identified by red oil) have become increasingly common. These leaks often appear around or underneath the main landing gear (MLG) pivots. The hydraulic fluid could be from either the wheel brake system or the landing gear retraction system. To help determine the source, it’s important to regularly check the fluid levels in the left and right brake master cylinder reservoirs and the landing gear power pack. Since both systems are connected to the MLG pivots, this simple monitoring can help pinpoint the source of the leak.

These external leaks are generally due to aged o-ring seals. The seals could be located in the MLG actuators or within brake system components, including the swivels in the pivot areas. You can often assess the severity of a leak by checking the oil’s texture — if it feels tacky, the leak is likely minor. This tackiness results from the evaporation of volatile components in the oil, leaving behind non-volatiles. In such cases, the leak can often be safely monitored for years, provided you maintain regular checks of the hydraulic reservoirs.

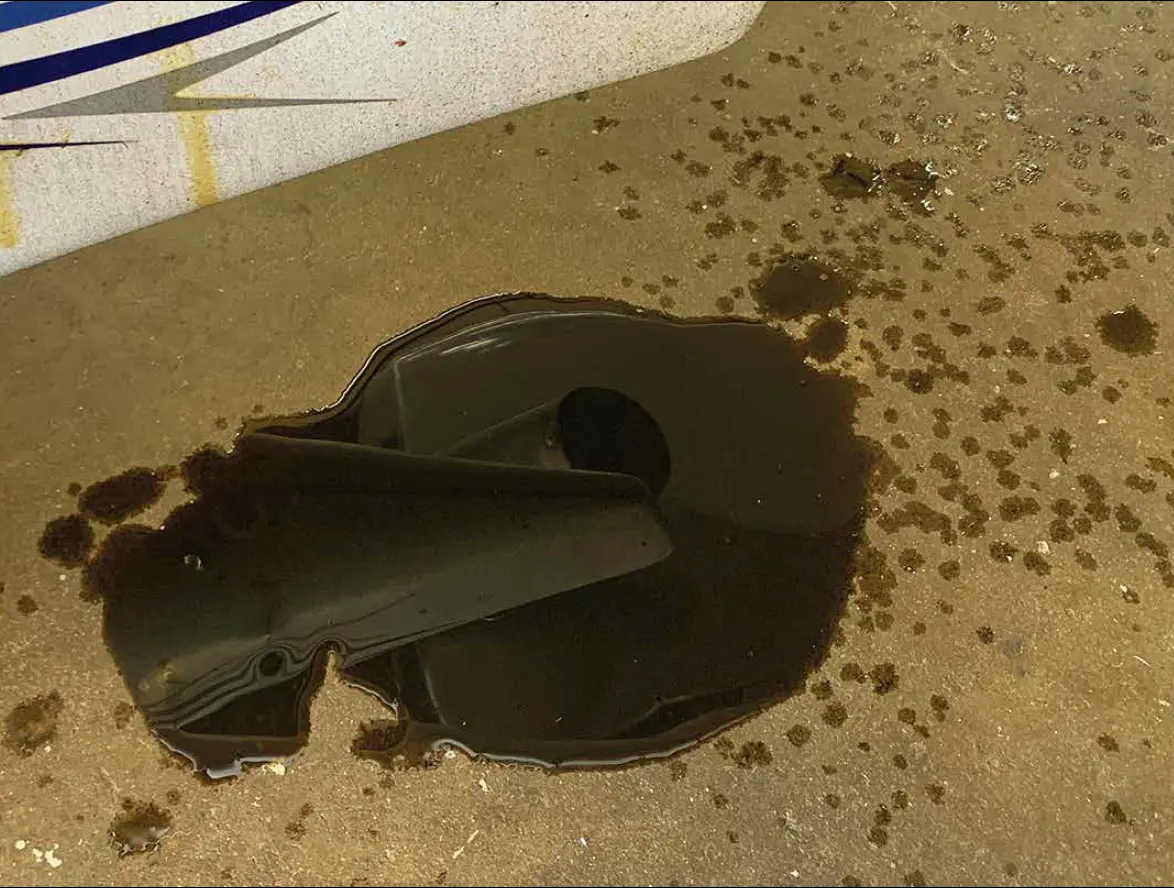

If, however, the oil is not tacky and appears fresh, the leak is of greater concern. In this case, close monitoring is advised. You may notice a pool of oil on a concrete floor beneath the aircraft. It’s wise to check and top up the affected reservoirs daily to track the leak’s severity. If the leak is manageable, you may be able to operate the aircraft cautiously through to its next scheduled maintenance.

While the aircraft parts manual doesn’t include a breakdown of the MLG wheel brake swivels, they can still be disassembled. This involves removing roll pins and a restraint ring to access and replace the common o-ring seal. If you’re unfamiliar with this process, it’s advisable to draw a quick diagram of the swivel assembly — especially the position of the o-ring and its backup ring — before disassembly.

The swivel joints play a vital role in maintaining the integrity of the MLG wheel brake hydraulic system during gear retraction and extension. For this reason, it’s wise to avoid applying brake pressure during gear cycling, as doing so increases load on the swivel o-rings. Replacing aged o-rings in the MLG pivots and actuators does require removing the MLG legs — a labour-intensive task. The upside is that these o-rings typically last about 40 years.

Wheel balancing is another frequently neglected practice following a tyre change. An unbalanced wheel can lead to premature wear and fatigue in key landing gear components, including MLG saddle pads and nose landing gear (NLG) downlock hook actuator pins. These issues can result in a false gear-down green light and even gear collapse. Nose wheel shimmy is caused, in nine out of ten cases, by an out-of-balance nose wheel or an out-of-round tyre.

Over the past 30 years, we’ve used two different dynamic wheel balancers. However, in the last two years we’ve found the static wheel balancing kit from McFarlane Aviation to be both quick and highly accurate.

If you know your wheels are out of balance, or you’re due for a tyre change, I strongly recommend asking for wheel balancing as part of the service.

Dynamic propeller balancing is another overlooked area that can significantly reduce wear and repair costs. An unbalanced propeller can cause fatigue to virtually every component on the aircraft — including the engine crankcase, baffles, oil cooler, avionics, instruments, lamps, and even the airframe itself.

If you’ve never had a propeller balance carried out — particularly if your prop has been dressed to remove nicks, repainted, or overhauled — I would highly recommend having one done. It’s a smart, cost-effective way to protect your aircraft and enhance the comfort of everyone on board.

By Tony Brand